Charles Dickens was deeply shaped by incarceration. When he was 12, his father lost his job as a pay clerk in the British Navy and was sent to debtor’s prison. His wife and children, except for Charles, soon followed. To survive, Charles was sent to work at Warren’s Blacking Factory where he washed and labeled jars of boot polish for 10 hours a day. He would later write that the ordeal left him feeling “utterly neglected and hopeless.”

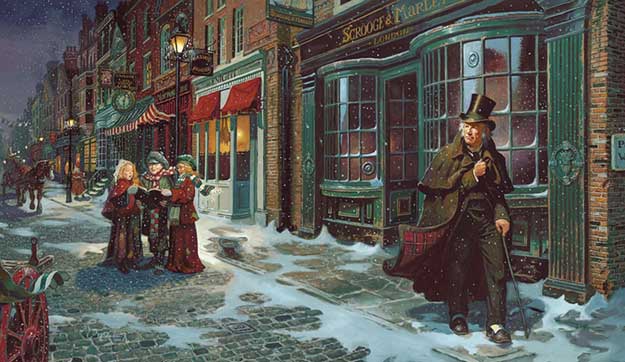

This experience fueled his lifelong critique of systems that treated the poor like outcasts and neglected the helpless. In 1843 London, the needy faced a multitude of challenges, including smog-filled skies, packed slums, and stark class divides. These conditions triggered him to write “A Christmas Carol” in just six weeks. Dickens channeled his righteous indignation into the character of Ebenezer Scrooge, who like many of the elites in society, saw the commoners as inferior and responsible for their own plight. Only after Scrooge meets the ghosts of his past, present, and future, does the trajectory of his life change.

The novella was published just before Christmas in 1843, and was an instant bestseller. Victorians called the book “a new gospel” because of Dickens’ vivid description of the deplorable housing conditions, overwork, and illness caused by substandard healthcare. His unflinching depiction of severe poverty, child labor, and the deep division between the rich and the destitute, challenged the harsh Victorian belief that it was the responsibility of the prisons and workhouses to care for the masses. The short story struck a chord with readers, and the initial printing of 6,000 copies sold out within a month.

Charles Dickens used storytelling the way the master storyteller, Jesus, does—not just to engage, but to reveal deeper truths about human life and morality. But Jesus’ parables are not just moral stories—they reveal Him as Savior, Shepherd, Judge, Healer and King. The central theme of “A Christmas Carol” is about redemption, and so is the birth of our Savior. Scrooge’s “rebirth” on Christmas morning is a literary echo of the spiritual rebirth offered in Christ, “If anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation; the old has gone, the new has come” (2 Corinthians 5:17).

Many prisoners, who remain captive to the power of sin and darkness in their lives, can say along with Scrooge’s former business partner, Jacob Marley, “I wear the chain I forged in life.” “A Christmas Carol” reminds us that no one is beyond redemption. In every outreach letter, every Bible provided, the Jailbird Ministry proclaims that same message.

“Men’s courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead,” said Scrooge. “But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change.”

Prisoners may feel trapped by the weight of their past, convinced that their future is already written. But just as Scrooge’s grim future was not etched in stone, neither are the lives of those behind bars. In Christ, their story can be rewritten. And isn’t that what Christmas is all about?